What a difference a year can make. At this time last year, the computer industry was at the beginning of a slowdown in sales of enterprise resource planning (ERP) software, which subsequently rippled through the IT industry and wreaked plenty of havoc on the financial results of application software vendors, IT services suppliers, and big hardware vendors like IBM. Only five months ago, in the January issue of MC in my Midrange Insights column, I presented an overview of the ERP, supply chain management (SCM), and customer relationship management (CRM) software markets that showed, according to research performed by AMR Research, that the ERP markets were expected to rebound in 2000 along the same revenue curves that AMR had predicted back in June and July of

1999. Those revenue curves, which many companies have based their business models on, were a little less optimistic than the curves the company presented in late 1997 and early 1998, but they showed a return to the more than 35 percent annual growth in ERP software sales. Well, according to the latest AMR numbers, that rebound is not going to happen exactly as forecasted.

That there would be a slowdown in ERP software sales in late 1999 was never a question in anyone’s mind. It made perfectly logical sense that the ERP sales growth we all saw in 1997 and early 1998 would abate, because we all suspected—no matter how much ERP vendors said otherwise—that the booming ERP market was really being driven by Y2K fears, just as the peak 1997 and 1998 server sales for IBM in the AS/400 and S/390 markets were an enthusiastic embrace of those platforms not by new customers but by existing customers who needed to buy extra capacity to support growing workloads alongside Y2K remediation projects. The evidence suggests that big IBM shops bought capacity well ahead of ERP software in late 1997 and early 1998, and only now has that capacity been absorbed by new workloads in the aftermath of Y2K projects that were more or less finished six to nine months ago in most AS/400 and S/390 shops. As I said in January, many AS/400 observers believe that a rebound in the AS/400 server market will be driven by a rebound in ERP software sales this year, but I warned that this may not happen. Six months later, it now looks like ERP sales will not grow as much as many had hoped, and this has important implications for IBM, AS/400 customers, and Business

Partners—and for anyone else who secondarily feeds off the substantial amount of money that midrange customers plough into ERP projects every year.

First, let me review what happened in the AS/400 market in the late 1990s and then take a look at AMR’s revised estimates for the ERP, SCM, and CRM software markets. In 1996, just as ERP software was coming into vogue, competition among ERP vendors and server vendors made it possible for more customers to buy ERP suites affordably. This drove overall revenues among the top ERP vendors (there are about 100 or so of them today) up to $7.2 billion. In that same year, IBM finally got the first-generation RISC- based AS/400s, which included Cobra and Muskie servers, to market, and pent-up demand for these machines drove AS/400 sales up 32 percent to $4.5 billion to make 1996 one of IBM’s best years ever in the midrange market. These RISC AS/400s were so popular because they offered incredible bang for the buck compared to earlier generations of AS/400s and because they offered unheard-of performance. The Muskie AS/400s were truly IBM’s first mainframe-class AS/400s. In 1997, the ERP market grew by an incredible 66 percent to $11.9 billion as new customers came into the ERP fold—in part to avoid rewriting their applications to become Y2K-compliant—and as existing ERP companies expanded from their initial users in the accounting department and on the manufacturing floor to include users in order entry, human resources, marketing, and other areas. But AS/400 sales in 1997, at $3.3 billion, were on the downswing, even as ERP sales were skyrocketing, partially because customers had bought so much extra power by moving to 4XX and 5XX AS/400 servers and partially because ERP solutions were increasingly being implemented on UNIX and Microsoft Windows NT platforms rather than on AS/400s. In 1998, AS/400 sales were again flat at about $3.3 billion while ERP sales rose by 34 percent to $14.7 billion. Last year, according to very preliminary estimates made by AMR Research as we went to press in early May, ERP sales were up a meager 8 percent thanks to Y2K lockdowns and the consequent ERP slowdown that was caused by those lockdowns and by customers revising their strategies away from ERP and toward e- business. And AS/400 sales were as low as they have ever been in their history at $2.6 billion. Last year’s AS/400 sales were so bad that IBM made more money in the first six months following its June 1988 AS/400 launch selling systems and 9332 and 9335 disk subsystems.

There’s an interesting trend buried in the AMR numbers: License fee revenues and overall ERP vendor revenues are not in lockstep when it comes to growth. In 1996 and 1997—when overall vendor ERP sales (meaning the software license fees and services revenues that went to ERP vendors rather than to their implementation partners) were growing at rates that even optimists had not predicted—these overall ERP sales were growing considerably faster than actual ERP license sales. In other words, one of the big drivers behind the ERP boom was not the desire by companies to use the software but the need to customize it once they decided to use it. In 1996, about 52 percent of the $7.2 billion in worldwide ERP revenues came from new software license fees or upgrades to installed ERP modules. License fees accounted for only 45 percent of the $11.9 billion in ERP sales in 1997 and the $14.7 billion in ERP sales in 1998. And while the overall ERP market grew by 66 percent in 1997 and by 23 percent in 1998, ERP license revenues grew by only 44 percent in 1997 and by 24 percent in 1998. In 1999, according to preliminary research by AMR that is subject to change, overall ERP sales were indeed up by 8 percent, but license sales actually declined by 3 percent to $6.5 billion.

What has happened to the ERP market to stifle its stellar growth? A couple of different things occurred, and they have combined to put a cap on potential ERP sales growth. AMR’s original projections back in late 1998, just as the Y2K-related ERP slowdown was becoming apparent, suggested that companies would weave ERP more intimately into their company and IT budgets because ERP could provide cost savings through organizational efficiency. But then along came e-business, where it has increasingly become apparent that it is more important to retain existing customers and expand to new ones through the Web than it is to shave a few points off the cost of a

transaction by implementing ERP. IBM and other prominent e-business vendors wanted customers to focus on e-business, and many of them are now doing that to the chagrin of ERP vendors that were not exactly ready with e-business extensions to their products. They have spent the past few years dealing with an ERP bubble and with the Y2K troubles of their customer bases and, having made billions of dollars, have come into the new millennium only to have the rug pulled out from under them.

The latest revised estimates from AMR for the size and growth of the ERP market are quite dramatic. For one thing, AMR is no longer projecting revenues into 2003. While its predictions have been pretty good throughout the 1990s—if anything, the ERP bubble in 1997 and 1998 caught AMR off guard and made analysts conservative in their estimates—we are in a whole new market now, and it is not only unwise but also impossible to predict too far into the future with any accuracy. In my opinion, any model of the IT industry has a very short time horizon these days, and AMR is implicitly concurring with this viewpoint, since it is now predicting only to the end of 2000.

As Figure 1 shows, AMR reckons that the overall vendor ERP market will grow in 2000 by 16 percent to $18.4 billion. This is a far cry from the 37 percent growth and $27.7 billion that AMR was projecting for the ERP market last summer. For 1998, 1999, and 2000, AMR is reducing its worldwide vendor ERP revenue estimates by a total of $15.6 billion. That is a lot of money that has just disappeared from the estimates, and considering that ERP and related software sales drive anywhere from 35 to 40 percent of AS/400 sales in a normal year—if we will, indeed, ever see one of those years again before the e- business transformations at small and midsize businesses the world over are complete—having those potential ERP sales that AMR reckoned were possible last year suddenly evaporate is a very traumatic thing.

So e-business has been the first factor that has diminished the prospects of ERP vendors this year. Oddly enough, it appears that the most popular adjuncts to ERP software—SCM and CRM extensions to ERP suites, often coming from ERP partners, not from ERP vendors themselves—have taken away money that companies might have otherwise spent on ERP projects. For decades, ERP vendors have been talking about the benefits that companies could derive if they invested in the core financial, manufacturing, and distribution programs that go into an ERP suite. (ERP was called MRP and MRP-II back in those early days, but the idea of tightly integrated software modules that run a business much as process controllers run a soup factory or nuclear power plant is not new. With ERP, all that has really happened is that software has been extended to all parts of the business, not just accounting or the shop floor or the warehouse.)

For the past few years, ERP vendors have been hawking the idea that ERP users now have to concentrate on extending their systems out to their partners with SCM suites and out to their customers with CRM suites—and companies appear to be agreeing with them. Unfortunately, they appear to be doing this with the money they might have otherwise spent on ERP software. This is why many of the big ERP vendors have bought SCM partners. (J.D. Edwards & Company bought Numetrix and PeopleSoft bought Vantive last year, just to name two.) And just about everybody is partnering like crazy with all the CRM vendors, especially industry juggernaut Siebel Systems, which is IBM’s new best buddy but which has yet to deliver a native AS/400 CRM solution. (It has promised to do that by the end of this year.) Anyway, the SCM and CRM markets, as far as AMR Research can tell, will resume their good growth in 2000. The SCM market got a bit of a haircut in 1999, growing by only 21 percent to $3.7 billion compared to the 50 percent growth AMR forecasted for 1999 back in mid-1998. The point is, the SCM and CRM markets should be growing at more than 45 percent this year and should together constitute more than 30 percent of the total ERP-SCM-CRM vendor revenue stream of $29.2 billion. That’s a lot of software sales, and it will drive a lot of server, middleware, and services sales, too. Hopefully, the AS/400 will get its fair share of server sales.

In 1999, according to preliminary research by AMR, the AS/400 did not do well against UNIX and Windows NT platforms when it came to ERP software license sales. As

Figure 2 illustrates, the contrast between the AS/400’s position in the ERP market in 1996, when the ERP bubble had just started to grow, and its position in 1999, when the ERP bubble burst, is striking. As the pie chart shows, in 1996, the AS/400’s share of the ERP license pie was 20 percent, but, in 1999, it was a meager 11 percent. The AS/400 is not the only platform that has lost market share. In 1996, UNIX-based ERP licenses accounted for about 60 percent of license sales, and, by 1999, they had dropped to 46 percent.

The platform that appears to be defying gravity when it comes to ERP is Windows NT, and it is the increasing importance of Windows NT as a credible ERP platform that is the third factor that has contributed to diminished ERP sales. In 1996, multiuser Windows NT platforms accounted for 12 percent of ERP license sales, and, by 1999, Windows NT had grown to account for 34 percent of total ERP license sales. That’s right. Last year, ERP vendors sold three times as much NT-based ERP software as they did AS/400-based ERP software and four times as much as UNIX-based licenses. In many cases, ERP vendors have positioned their NT packages to be less costly, even if they are missing some of the features of their UNIX and AS/400 counterparts in their catalogs, often in an attempt to go after smaller midrange customers than they could profitably chase with their high-end AS/400 and UNIX ERP software lines. Moreover, NT hardware platforms, systems software, and middleware have all matured to make NT more credible. When all these forces are coupled together, it is not surprising that there has been a huge upsurge in Windows NT ERP sales. Figure 3 shows worldwide ERP license revenues by platform in billions of dollars from 1996 to 1999. What it shows is that, based on revenues, the UNIX portion of the ERP market held steady at $3 billion between 1997 and 1999. The AS/400 portion of the pie grew steadily at about 35 percent in 1997 and 1998 but was cut in half in

1999. Sales of ERP licenses on Windows NT platforms increased by 150 percent in 1997 and 80 percent in 1998 and were up only 11 percent in 1999.

What’s the upshot of all this? Well, based on the AMR numbers, it looks like the AS/400 platform bore the brunt of the ERP slowdown. If you find these numbers disturbing, so do I. I am not certain whether this means that AS/400 customers were buying way ahead in the ERP market compared to UNIX or NT customers or that there was a big shift away from the AS/400 when it came to ERP. Odds are, the AS/400 ERP market will rebound in 2000. But chances are that the AS/400 will not have the market share that it enjoyed in the mid-1990s. Even if AS/400 ERP sales were to rebound to 1998 levels, UNIX and NT ERP sales will, by my estimates, be nearly three times as large as ERP license sales on AS/400s. AMR, of course, is not comfortable making estimates by platform at this point in the turbulent ERP market history but was pretty certain last year that AS/400 sales would lose a point of market share per year in the foreseeable future. AMR did not foresee the dramatic drop of AS/400 ERP license sales in 1999, and neither did anyone else, so it is completely understandable that no one wants to make emphatic statements in this regard. By this time next year, we will see how it all works out.

$20 B

$15 B

$10 B

$5 B

$0 B

CRM Sales SCM Sales ERP Sales

Source: AMR Research

1997

$1.2 B $1.8 B $11.9 B

Worldwide Vendor Revenues

1996

$0.8 B $1.1 B $7.2 B

1998

$2.3 B $3.0 B $14.7 B 1999

$3.8 B $3.7 B $15.8 B 2000

$5.5 B $5.4 B $18.4 B AS/400

UNIX

Windows NT

Others

Figure 1: ERP, SCM, and CRM vendor sales have grown considerably in the past few years.

9%

8%

60%

11%

12%

Source: AMR Research

Inner Ring: 1996 ERP License Revenues Outer Ring: 1999 ERP License Revenues

20%

34%

46%

Figure 2: The AS/400’s piece of the ERP pie has been shrinking and did so rather dramatically last year.

$4 B

$3 B

$2 B

$1 B

$0 B AS/400 UNIX Windows NT Others

Source: AMR Research

1996

$0.8 B $2.3 B $0.5 B $0.3 B

Worldwide ERP License Revenues

1997

$1.0 B $2.9 B $1.1 B $0.4 B 1998

$1.3 B $2.9 B $2.0 B $0.4 B 1999

$0.7 B $3.0 B $2.2 B $0.6 B

Figure 3: AS/400-based ERP sales plummeted in 1999 while ERP sales on UNIX and NT platforms more or less held steady.

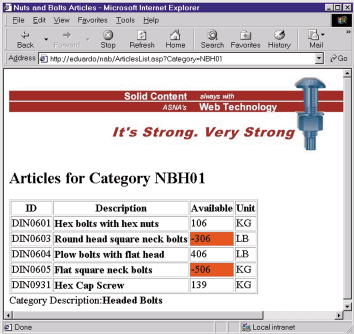

Figure 3: The transformation from XSL into HTML gives this browser display.

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online