As iSeries programmers, we are accustomed to writing programs that produce some kind of printed output. If I asked you what you use for a "quick and dirty" report that requires no special calculations, you would probably say you use either Query/400 or Query Manager/400, as most of us do. Here's one for you: What tool would you use to print a copy of your "Powered by Apache" Web server configuration, a text file located on your IFS? Ah, you're not as quick to respond in this case, are you?

Let's change the scenario to make it a request to print a configuration file on a Windows platform. (Yes, this is a contrived example, since most Windows configurations are stored in that ill-conceived receptacle known as the registry.) How would you do it? This one is probably easier to answer. Most of you would open the file in WordPad and print it from there, which is what you would use for most of the text files you need to work with while in Windows.

Now, let's move to the Linux OS. How would you print a configuration file (or other text-based file) while in Linux? Are you falling back on the old Windows-style standby of using an editor, such as VI or EMACS, or a word processor, such as that found in Open Office? There are more elegant means available than to use a heavy-weight program, and they are the topic of this month's column.

The UNIX Way

As I have said many times in my column, the UNIX (and therefore Linux) design philosophy is to write programs that do one thing and do it very well. Typically, these single-task programs are strung together in a chain whereby the output of one program becomes the input of the next. And that output is typically simple ASCII text, as are the Linux configuration files. (Binary config files need not apply!) It should come as no surprise that with all of that text flying around, many light-weight programs have been written to manipulate and print it. I'll discuss two of them in this article.

PR

The first single-purpose program that we'll examine is the venerable pr utility, which was written during the era of kerosene computers, when printers didn't require drivers to produce legible output. You simply sent ASCII text to them. Of course, that meant formatting had to be simple: space, carriage return, line feed, and form feed.

In typical UNIX fashion, pr takes input from stdin or any text file(s) and outputs to stdout. The utility's purpose in life is to add some basic formatting to text files. The easiest way to describe pr is simply to show some examples, so I have created three simple text files: file1.txt, file2.txt, and file3.txt. They have similar content, and the content of file1.txt is below:

This

is

from

file

1

[klinebl@laptop2 current]$

Let's see what pr will do with this file:

|

As you can see, pr has placed the date, time, file name, and page number on the heading. So as to more readily fit the output into the confines of a Web page, I have instructed pr to assume a page width of 70 characters (-W 70) and a page length of 15 lines (-l 15). Normally, pr would assume a width of 72 characters and a length of 66 lines.

What if you'd like to see all three files side by side? Simple. Include the "-m" merge option on the command line, and pr will happily oblige, as shown below:

|

Had you not included the merge option (-m), the previous command would have printed each file on its own page. A great use for that is to print a copy of all of your system's configuration files. These are stored in the /etc directory and can easily be printed en masse via this command:

As I explained in last month's article, the Find command examines a list of files and returns any that match your criteria. Thus, the command shown above lists all regular files (-type f) with an extension of ".conf" (-name "*.conf") that are located in the /etc directory and then pipes them to the xargs command, which builds and executes the pr command. Once you have amassed your listings, you could keep them up-to-date on a weekly basis by adding the "mtime" switch to the command:

This command will list files that have been modified within seven or fewer days.

One last thing about pr: All it does is basic formatting. To actually print the results, you need to pipe the result to lpr, like so:

Of course, you can capture the output and redirect it to another file if you'd like:

A2PS

While pr is fine for basic formatting, its output is simple text. Most printers in today's world are capable of much nicer output when spoken to in PostScript, Printer Control Language (PCL), or in the case of the brain-damaged printers available at your local discount store, some proprietary language (requiring a special driver). To make your output even prettier, you can turn to tools such as enscript or a2ps. Red Hat Linux will have already included a2ps if you selected printing during the installation of the package. Enscript is also available with Red Hat Linux, but you'll need to install it separately. Both serve roughly the same purpose, so I'll discuss only a2ps.

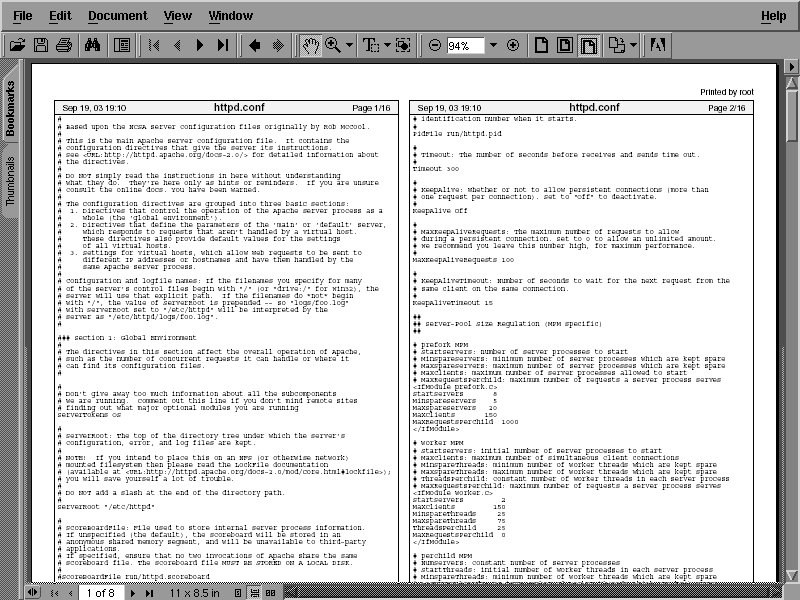

Essentially, a2ps is pr on steroids. It does all of the formatting that pr does, but as you can probably guess from its name, a2ps takes as its input ASCII text and produces as its output PostScript. Once again, a picture is worth a thousand words, and in this case, I need to provide a picture. Remember, I asked earlier how you would print the configuration file for the Apache Web server from your IFS. I'm not connected to my iSeries as I write this, so I'll need my laptop's Web server configuration to be a proxy for the real thing, but the results will be the same. Figure 1 below shows the result of this command:

a2ps -o - -A fill /etc/httpd/conf/httpd.conf | ps2pdf - /tmp/test.pdf;acroread /tmp/test.pdf

Although the command line is somewhat daunting, it's actually quite simple. These are the switches to a2ps:

- -o - (output to standard out)

- -A fill (fill the page left/right)

- /etc... (the file to print)

- | ps2pdf - /tmp/test.pdf (pipe to the ps2pdf program, which will get its input from stdin and output the results to /tmp/test.pdf)

The semicolon separates the first command from the second, which calls the Acrobat Reader program to display the file. I had to do this conversion to get a PDF to read on my machine so that I could include it in this article. Had I not specified stdout, the program would have automatically sent the results to my default printer.

Figure 1: The output from a2ps is very attractive.

As you can see from the result, the output of a2ps is really quite nice, almost suitable for framing! Included among the many available options are portrait or landscape printing, the number of copies to print, the number of pages to print per page (e.g., 2-up, 4-up, etc.) and, if you'd like, you can even generate a table of contents if you have asked to print multiple files. Not bad for a command line utility, is it?

Think Outside the Box

Both of the utilities I mentioned take text as input, so don't think that you're limited to manipulating files with them. The output of most UNIX commands is plain text, so you can use their output as input for your printed output. For example, I have one client who receives a daily email summary of all phone calls taken by the answering service. This summary is printed and routed through a couple of departments before being marked up and inserted into a book for permanent storage. To avoid manual printing, I set up an email address on one of my Linux servers to be the target for that email. When it arrives, it is piped to the a2ps command for printing. That way, it automatically appears on the printer every morning, without fail.

A Note about PostScript

The Adobe corporation really did a nice job when it conceived of the PostScript printer language. PostScript is a plain-text language, so you could, if you wanted to, get your printer to sing and dance via a simple text editor. As a result of this open standard, programs such as ps2pdf (which I used to generate the example) and the various PostScript viewers are easily written. Although PostScript is strongly supported in Linux, Hewlett Packard's PCL is also a viable alternative. It, too, is a text-based language, so you could conceivably handwrite a PCL program that your printer would understand. The brain-dead printers that I alluded to earlier (a.k.a. WinPrinters) are frequently supported in Linux via a driver. For detailed information about the mechanics of Linux/UNIX printing, visit the Linux Printing Web site.

A Good Read

I have frequently been asked to suggest a book that can help improve one's UNIX skills. Since it's December, I thought it fitting to answer that question here so that you can put this book on your holiday gift list. The reigning king (in my opinion) is Unix Power Tools (ISBN 0-596-00330-7). Whenever I'm tackling a project and wonder, "Gee, has a utility or solution to problem X been addressed before?" I simply pull out my copy and usually find what I'm looking for very quickly.

That's it for this month. I wish everyone a safe and happy holiday season. See you next year!

Barry L. Kline is a consultant and has been developing software on various DEC and IBM midrange platforms for over 20 years. Barry discovered Linux back in the days when it was necessary to download diskette images and source code from the Internet. Since then, he has installed Linux on hundreds of machines, where it functions as servers and workstations in iSeries and Windows networks. He recently co-authored the book Understanding Linux Web Hosting with Don Denoncourt. Barry can be reached at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online