The IT industry is putting an emphasis on automation. The Ruby on Rails web framework has been doing that for a decade. Ride this rail with me as we dive into the many cool realities of Ruby on Rails.

In the February 2015 article "Trying on a Ruby Ring," I talked about doing a small Hello World Ruby app and showed how to invoke an RPG program from Ruby. In March 2015's article "Sinatra Sings, Ruby Plays," I introduced you to a very simple web framework named Sinatra. In the April 2015 article "Ruby Talks to DB2 for i," I showed how a simple Ruby web application can query DB2.

Some of those articles touched briefly on portions of the Ruby on Rails web framework (Rails for short). We are about to embark on a journey to further define the many benefits of Rails and see why so many other technology stacks have followed their lead over the years.

So, what is Rails?

Instead of giving a canned Wikipedia definition, I will instead ask a question. Do you have tasks in your daily RPG duties that are repeated time and time again, requiring manual coding that you could write in your sleep (essentially "busy work")? That's what the creator of Rails, David Heinemeier Hansson, resolved to do after doing web development for a number of years. He spent too much time doing the same things over and over in his web apps. During that time, he started recognizing patterns of best practices. It was then he decided to write a framework to address the repetitious coding. Eventually, Rails was born.

It's time to kick the tires.

In this article series, we will incrementally build a database maintenance application in PASE on IBM i using PowerRuby. There are two ways to start coding on a Rails project. Either you are creating the application or coding in an application already created. The latter involves cloning a Git repository. We will be taking the approach of creating a new Rails application from scratch by using the rails new command, as shown in the log output below. Notice how Rails generates files and directories.

Note: I am running this in a PASE shell. It's best to use ssh to log into your IBM i. However, you can also get a PASE shell using CALL QP2TERM (the poor man's shell).

$ rails new app1 --skip-bundle

create

create README.rdoc

create Rakefile

create config.ru

create .gitignore

create Gemfile

create app

create app/assets/javascripts/application.js

create app/assets/stylesheets/application.css

create app/controllers/application_controller.rb

create app/helpers/application_helper.rb

create app/views/layouts/application.html.erb

create app/assets/images/.keep

create app/mailers/.keep

create app/models/.keep

create app/controllers/concerns/.keep

create app/models/concerns/.keep

create bin

create bin/bundle

create bin/rails

create bin/rake

create config

create config/routes.rb

create config/application.rb

create config/environment.rb

create config/secrets.yml

create config/environments

create config/environments/development.rb

create config/environments/production.rb

create config/environments/test.rb

create config/initializers

create config/initializers/assets.rb

create config/initializers/backtrace_silencers.rb

create config/initializers/cookies_serializer.rb

create config/initializers/filter_parameter_logging.rb

create config/initializers/inflections.rb

create config/initializers/mime_types.rb

create config/initializers/session_store.rb

create config/initializers/wrap_parameters.rb

create config/locales

create config/locales/en.yml

create config/boot.rb

create config/database.yml

create db

create db/seeds.rb

create lib

create lib/tasks

create lib/tasks/.keep

create lib/assets

create lib/assets/.keep

create log

create log/.keep

create public

create public/404.html

create public/422.html

create public/500.html

create public/favicon.ico

create public/robots.txt

create test/fixtures

create test/fixtures/.keep

create test/controllers

create test/controllers/.keep

create test/mailers

create test/mailers/.keep

create test/models

create test/models/.keep

create test/helpers

create test/helpers/.keep

create test/integration

create test/integration/.keep

create test/test_helper.rb

create tmp/cache

create tmp/cache/assets

create vendor/assets/javascripts

create vendor/assets/javascripts/.keep

create vendor/assets/stylesheets

create vendor/assets/stylesheets/.keep

Log output: Wow, that's a lot of created files!

So what just happened? The rails new command uses the first parameter as the name of your application, app1 in this case. The option --skip-bundle is declaring we don't want the bundle command to run, which would go out to the Internet and download the latest versions of Rails. PowerRuby gives us everything we need to write Ruby applications, so there's no need to download additional components (yet).

Why did the creators of Rails determine these directories and files should be created? This is where I'll introduce the Rails concept of Convention over Configuration, or CoC for short. CoC goes back to the heart of why David created Rails. He found the majority of web apps all need to have the same base directory structure, the same configuration files with default settings, so on and so forth. By running that single command to generate all those files and folder, we probably saved the better part of a couple hours. The actual completion time was under 5 seconds! You'll see CoC mentioned frequently throughout this article series.

Now let's go further into the generated files and directories. The first file of significance is Gemfile, a configuration file that uses the Ruby language syntax. This stores all of the dependencies of our Rails application and is shown below.

source 'https://rubygems.org'

gem 'rails', '4.1.8'

gem 'sqlite3'

gem 'sass-rails', '~> 4.0.3'

gem 'uglifier', '>= 1.3.0'

gem 'coffee-rails', '~> 4.0.0'

gem 'jquery-rails'

gem 'turbolinks'

gem 'jbuilder', '~> 2.0'

gem 'sdoc', '~> 0.4.0', group: :doc

gem 'spring', group: :development

As you can see, the Gemfile lists out all the Gems (think of Gems as RPG *SRVPGMs) and versions that our application makes use of. This serves two purposes. First, it keeps a running tally of the various Gems used in our application. Second, it is reviewed when deploying to production. When you deploy to production it will look at Gemfile and compare the Gems listed to the ones that exist on the local machine. If it is lacking any Gems, it will then download them from the URL specified on the source line. This is some nice automation that's a huge timesaver.

Interesting tidbit: HelpSystems recently sent out their 2015 survey results, which indicated automation was one of the priorities IBM i shops are looking at. Rails has had it for a decade. This is a good train to get on, folks!

Next in the log output, we see the app/assets directory and subdirectories being created. This is where your static client-side CSS and JavaScript will be stored. Likewise, we see directories created for app/controllers, app/models, and app/views. These correlate to the MVC (Model-View-Controller) concept of separating out portions of the application. To relate this to RPG, think of the Model as *SRVPGMs, where you do business logic and database access. Think of the View as your *DSPF DDS. And think of the Controller as your RPG mainline program, where you have your EXFMT and monitor for user key presses.

Next in the log output, we see many directories within the config directory. There are many configuration purposes served in here. I will highlight a few and will expound further in subsequent articles. The routes.rb is used to declare how browser requests should be routed to corresponding controllers. The environments directory has three files: development.rb, production.rb, and test.rb. Rails assumes that each application will, at minimum, need three different environments to configure the application. For example, when the application is being run in development, you will want errors to display in the browser. However, you wouldn't want the same in production for your customers to see. There's a setting for that. There are many more environment-specific settings that allow you to fine-tune. The most common settings are set for you. Note, it is very simple to add additional environments. One I usually add is called "staging"—a deployment that allows select users to test before deploying to production.

File config/database.yml contains the database configuration for the three environments (development, test, and production). In this case, our application is using the SQLite database. We will convert it to use DB2 in a subsequent article.

The last thing I want to point out in the log output is the test directory. To describe this directory, I will describe my days doing RPG-CGI (web) development. When I deployed to production, it was always with a decent amount of anxiety because I didn't have unit tests for my APIs and web pages. This meant I often deployed in the evenings or on the weekends. With Rails, unit testing is not an afterthought and instead was included from ground zero.

Interesting stat: Amazon deploys their apps to production every 12 seconds (they obviously have many apps). Do you think they are able to do that without automated unit testing? No!

The rails new command has actually created enough foundation that we can start our application and see a "Hello World" page. PowerRuby comes bundled with an application server, so we don't need to set up Apache or other to get it working.

Before we do start the Rails webserver (and depending on which PowerRuby version you are using), you may need to add the following line to your Gemfile file:

gem 'tzinfo-data'

And whenever you add something to your Gemfile file, you also need to run the bundle command, as shown below:

$ bundle install --local

At this point, we are still outside of the app1 directory that was created with the rails new command. To run additional commands against the Rails app, we need to be within the directory by using the cd command. Then use the rails server command to start the application.

$ cd app1

$ rails server -p 8080

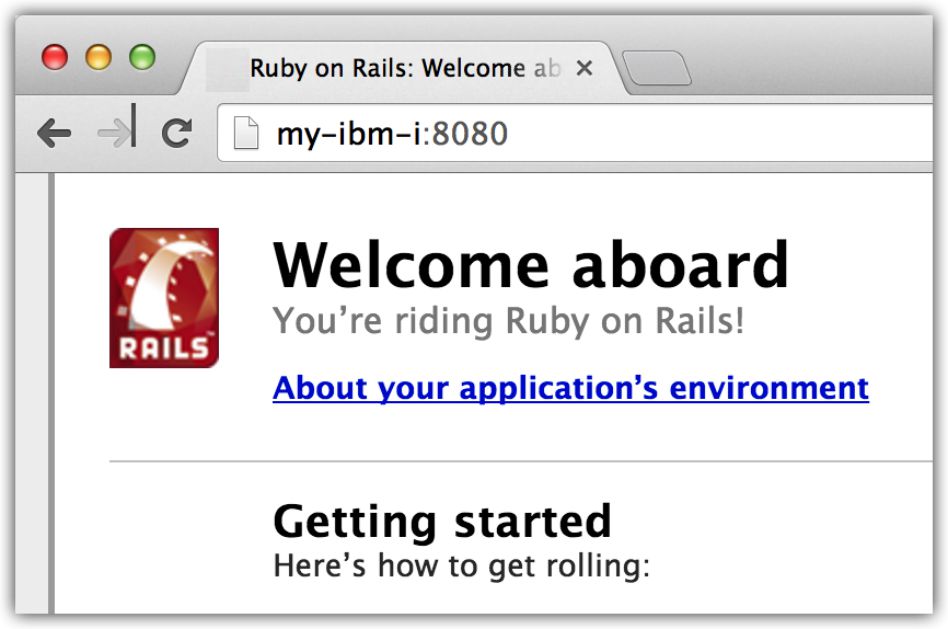

Open your browser and point it at port 8080 of your IBM i IP address. You should see something like Figure 1.

Figure 1: Rails server is started and running.

That concludes this first article.

I hope I've piqued your interest enough to start exploring Ruby on Rails. We've only touched the tip of the iceberg! If you need an IBM i sandbox to start getting your hands dirty with Ruby on Rails, please contact me and I'll hook you up!

If you have any additional questions please let me know in the comments or reach me directly at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online