The proliferating adoption of open source on IBM i means there's a lot going on in PASE. How does one keep from stepping on toes? "IFS Containers" to the rescue.

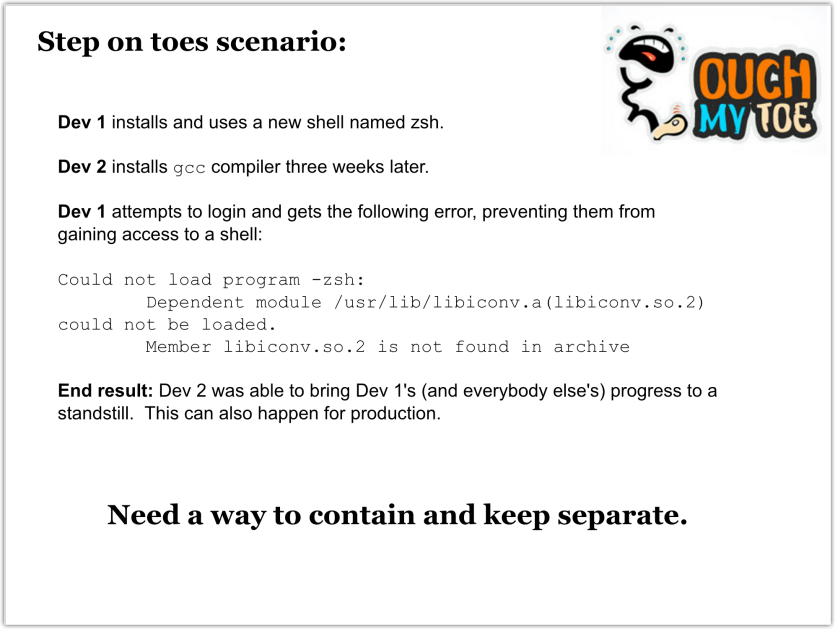

I was talking with a colleague the other day, and he gave me valuable feedback, stating I should do more at the beginning of articles to describe the problem or the usage scenario of the technology before I jump into the geek parts. Of course, that's priceless feedback for me because if people don't understand the "why," then they won't take the time to read. So let me start this article with a slide that describes a common scenario with shops adopting open source on IBM i (Figure 1). BTW, this entire slide deck is available here as are all of my slide decks.

Figure 1: “Step on toes” scenario

In short, Figure 1 describes a scenario where two developers are working on the same machine and do something to cause the other's development environment (or complete access to the machine) to be hindered. The same can happen with RPG: Two developers, unaware of the other’s work, could develop RPG *SRVPGMs that export the same-named subprocedures. Then if either developer’s library list isn't set correctly, that developer could pick up the other developer's same-named subprocedure. And things would bomb out.

How could this situation be remedied? You could give each developer their own virtual instance of IBM i, but that might get expensive on both licensing and maintenance. On the RPG front, most shops have guidelines they've set forth. It actually isn't nearly as big a problem in RPG because RPG open source isn't as plentiful, so there's not as much opportunity for conflict by those "outside your control." It's not so simple when we get to the PASE environment because many of the collisions are because of third-party open-source software. In the aforementioned example, there was a conflict between software obtained from perzl.org and the equivalent library (libiconv.a) delivered with the IBM i operating system. So again, how can this situation be remedied without spinning up an entirely new IBM i? Enter what I call "IFS Containers."

IFS Containers is a term I've coined to describe the concept of what happens when you use the PASE chroot command. (More on the chroot command later.) Imagine if you could create a container in the IFS that would keep one container from even knowing other containers existed (i.e., they can't see other parts of the IFS outside their own container). That means that if a developer installs a new tool, it will affect only their specific container.

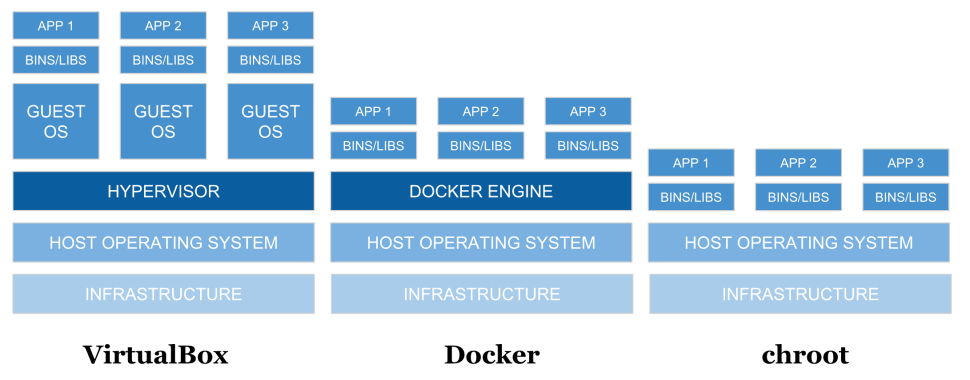

Containers are not a new concept. There are many containerization technologies, such as VMWare, VirtualBox, Docker, etc., and there is a different approach for each style. Figure 2 compares three approaches in visual form.

Figure 2: Comparison of different approaches

You'll notice they all start out with the same infrastructure and host operating system layers. The next layer is where things change. First, let's look at the Virtualbox stack. Virtualbox has what's called a hypervisor, a piece of software used to control operating systems running on top of the host operating system. These are full copies of the operating system that don't share a common operating system. I've used this extensively over the years to run a virtual Windows desktop on top of Linux and Mac, and it works quite well. A similar hypervisor is Parallels, which is popular with Mac users. The next level of VirtualBox after the guest OS is the "bins/libs," which are basically the various runtimes and supporting libraries. These would be things like language and tool binaries (e.g., node, php, ruby, python, java, openssl, git, etc.) and the supporting libraries would be things like libssl, libcrypto, libc, etc. And finally we have the app layer. This is the code of your application and any frameworks (e.g., RubyOnRails, ExpressJs, Django, ReactPHP, etc.).

Next, let's look at the Docker stack. Instead of a hypervisor, there is the Docker Engine. This engine does similar things to a hypervisor—like allocation of memory and disk—but there's one significant difference: Everything is running on a single instance of the operating system. Each of the three stacks above Docker Engine is a Docker container that houses a specific set of binaries and libraries, yet they all make use of the same base "kernel" operation system. Even though each of those containers is looking at the single kernel, each container has its own set of process ids (aka IBM i job number), users, and control groups for CPU and memory. For example, this means you could have a user named Joe in each of the containers, each with a completely different definition of that user (i.e., permissions). For those familiar with iASP technology on IBM I, this is the opposite of how that works; specifically, *USRPRF objects are stored in *SYSBASE and must be unique across all iASPs on that instance of IBM i.

OK, so now we've learned a bit about Virtualbox and Docker, but what about the chroot stack? As you can see, it doesn't have a hypervisor or Docker Engine. That’s because chroot is much simpler in nature in that it only contains, or keeps separate, the file system—hence the "IFS Containers" moniker. I only use that term to create a visual picture in your mind because there aren't actually separate file systems. It's time to further describe what the chroot command does.

The chroot command stands for "change root," or rather, when I run the chroot command and point it at an IFS directory, I can change the perceived root. At this point, it would be good to start getting into some tangible examples so you can see the chroot command in action.

First let's learn the syntax for the chroot command, as shown below.

$ chroot Directory Command

Here are the descriptions for Directory and Command:

· Directory—Specifies the new root directory

· Command—Specifies a command to run with the chroot command

Armed with that knowledge, let's log into the IBM i via SSH (CALL QP2TERM could also be used to enter a PASE shell) and attempt to run the chroot command on a newly created directory named dir1.

$ ssh aaron@myi>

After I run the ssh command on my local Mac, I am then logged into PASE on the IBM i. The prefix of "bash-4.2" is telling me what shell I am using. I do a pwd so you can know where I am in the file system. I run the ls (list) so you can see the command working (more on this later). Then I create a directory named dir1 with the mkdir command. Finally, I get to the chroot command. I want to "change root" to dir1, and once inside the new root I want to run the ls command. As you can see, the ls command couldn't be found. But why not? Didn't ls exist when we first logged in? Herein we learn the primary concept of chroot (or IFS Containers).…

If you don't manually put something into the IFS Container, then it doesn't exist.

What does that mean? Well, when we ran the chroot command, it placed us inside the dir1 directory, and that became our new root directory. Once you’re placed inside the directory by the chroot command, you can't see anything else above the directory you're in. The chroot command then supplied the ls command, and it came back as not found because there aren't actually any files or directories inside of dir1 that made it capable of running the ls command. So let's add them.

bash-4.2$ pwd

/home/AARON

bash-4.2$ mkdir -p dir1/usr/lib

bash-4.2$ cp /lib/libc.a dir1/usr/lib

bash-4.2$ cp /lib/libcrypt.a dir1/usr/lib

bash-4.2$ mkdir -p dir1/usr/bin

bash-4.2$ cp /QOpenSys/usr/bin/bsh dir1/usr/bin

bash-4.2$ chroot dir1 /usr/bin/bsh

$ ls

ls: not found

Let's go through the above commands. First, I create a new directory where we can put some library files, namely libc.a and libcrypt.a, and then we copy those files into dir1. These two libraries are fundamental to being able to run commands once inside the IFS Container. Next, I determine we would want to enter the IFS Container and be given an interactive shell prompt, much like the shell we are now in. To accomplish this, we need to create a dir1/usr/bin directory and copy the bsh (Bourne Shell) into it. Now I run the chroot command again and this time specify the fully qualified path to bsh for the command portion of the call. At this point, I am inside the IFS Container and in an interactive shell. I run the ls command and it declares it still can't find it. That's because I neglected to copy it into the IFS Container. At this point, it's necessary for me to exit the IFS Container and copy the ls command into the IFS Container.

$ exit

bash-4.2$ cp /QOpenSys/usr/bin/ls dir1/usr/bin

bash-4.2$ chroot dir1 /usr/bin/bsh

$ ls /

usr

$ ls /usr

bin lib

$ ls /usr/bin

bsh ls

$ ls /usr/lib

libc.a libcrypt.a

Above, I show how to exit the IFS Container and then I copy in the ls command. Then, I enter the IFS Container again using the chroot command and successfully run the ls command (because it now exists inside the IFS Container). I then proceed to use the ls command to display the root of my IFS Container and the contents of the other directories. What's important to recognize is what is not there. Specifically, there isn't a /QSYS.LIB directory or any other directory, such as /home. I could create a /home directory, but you can't copy /QSYS.LIB into an IFS Container.

So how does this help the original scenario of developers stepping on each other’s toes? Note how the ls command wasn't able to see anything outside of the IFS Container. The same holds true for all other commands and programs in a chroot environment, which means if we were to install some software, it wouldn't be able to affect other directories because it couldn't reach or see those other directories. This is an incredibly useful feature, not only for development but also for situations where I want to quickly test a piece of software; once I am done, I can simply delete the IFS Container.

At this point, you might be thinking that creating IFS Containers might be a laborious thing to do because of the many things needing to be set up (we've only touched the tip of the iceberg). No worries, there’s open source code to help with that, and that is what I'll be covering in the next article. Stay tuned!

If you have any questions or comments, then please comment below or email me at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online