We all know we need to program for the Web, but we hear all kinds of stories about how hard Web languages are. This article compares two of the most popular options.

The Web beckons. The green-screen has been more than adequate for years, even decades, but the pressure for something more modern keeps building. If you don't figure out how to expose your business logic via some sort of browser-based user interface, the Windows crowd is going to demand a GUI solution. That means the business logic starts migrating away from RPG. Not long after that, the database itself follows, and it's goodbye IBM i. So you need a Web solution and you need it now, but how do you get there? Today I'll compare the fundamental characteristics of the two most popular options for the IBM i community.

This Article Is About 3GLs

I bet you thought this would be about EGL, didn't you? Well, surprise! Even though I find EGL to be by far the easiest language in which to develop Web applications, for the purposes of this article I'm going to stay away from 4GL solutions. Most tools today, whether it's a commercial solution like BCD or an IBM tool like EGL, build on some underlying language. Even ILE-only tools like IceBreak build on top of RPG.

I believe you should understand the underlying infrastructure for anything in your enterprise, so today we're going to assume you're going to roll your own solution from a 3GL. According to TIOBE, of the languages used for the Web, the two most popular are Java and PHP, and both are available on the IBM i. So let's start with Java. While this article is about Web programming, for the purposes of comparison I'm going to present snippets of code that compare the fundamental aspects of the languages.

Let's Start With Java

Figure 1: This simple Java code creates an abstract class, extends it, and then uses it. (Click image to enlarge.)

In Figure 1, you'll see some very barebones code that exemplifies the basics of object-oriented programming (OOP) in Java. In Java, you are supposed to model your code by modeling real concepts. In this case, I want to create an object that can calculate its own area. It's not Web-oriented to any degree or even business-oriented; it's just a simple example. But it illustrates some very pertinent concepts. First and foremost is the idea of a class. A class is an OOP concept that acts as a container for program logic. You segregate related code into a class and then use that class along with other classes to build your business logic. The nifty part about OOP is that you can reuse that code by extending the class. Extending a class (or "subclassing") means that I create a new class that inherits the behavior of the parent class. In this case, I have an abstract class called Shape whose primary attribute is that it has a size that can be set. The Shape class exposes a method called "setSize," which lets the programmer set the size. Shape also defines an abstract method named getArea. An abstract method is one that must be implemented by the children. An abstract class is one that is never instantiated directly; only its concrete children can be created. Typically, an abstract class defines the general characteristics common among several related children. In this case, all the shapes have a size, so we implement the size logic in the abstract parent class. The Square class is the concrete descendant of Shape. The minimum a concrete subclass has to do is to provide concrete implementations of the abstract methods. In this case, the getArea method implements this simple formula: area equals size squared. The top part of the figure shows an actual implementation of the code: it creates an object of type Square, sets the size to 2, and then prints the area.

You'll note that certain keywords are available to facilitate this development. Keywords like public, abstract, class, and extends have all been around in Java since its inception in the early 1990s. These keywords provide the fundamental underpinnings to all of the OOP capabilities of the language. The terms are similar to those in C++, but there are significant differences. For example, C++ uses the term "virtual" rather than abstract. Where Java defines the visibility (public or private) of each variable or method, C++ classes have defined sections in which all of the variables share the same visibility. The differences are primarily syntactic, but it's clear that Java was written specifically to support OOP, whereas C++ was more of a way to add classes to the already existing C language.

And Now for Something Completely Different—PHP!

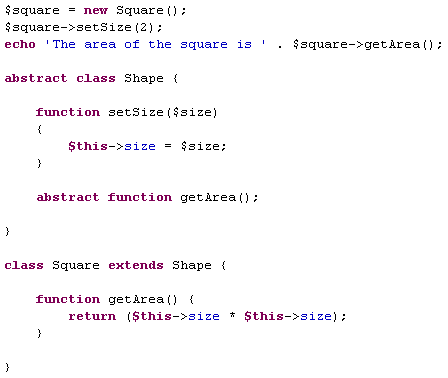

Figure 2: This is the same code as Figure 1, implemented in PHP.

Actually, the title of this section is a little tongue-in-cheek. If you look at the two code snippets side by side, you might be hard-pressed to immediately identify which is Java and which is PHP. Not only is the terminology the same, in many cases the syntax is similar or even the same. For example, defining the class Square as a subclass of the abstract class Shape uses exactly the same syntax: class Square extends Shape. When the new object model was added in PHP 5, it seems that they definitely took into consideration the popularity of Java.

You will notice a couple of syntactical differences. Java uses a dot (period) to denote a member variable or method (square.setSize) while PHP uses the "arrow" syntax ($square->setSize). The dot is already used in PHP to denote concatenation, so when OOP was added, they needed a different syntax. Another difference is that all variables start with a dollar sign ($). It's obvious what a variable is in PHP! Also, what Java calls a "method" PHP calls a "function." But these are primarily syntactical differences. Two other related differences are more subtle but more profound. First, nowhere in the PHP example do you see a definition of the variable $size. This is absolutely anathema to Java, which, like RPG, requires every variable to have a specific compile-time definition. This is called "static" typing, and Java is a statically typed language. PHP is not. PHP is a dynamically typed language, and this manifests both in that you don't need to specify variables at compile time and also that you don't need to specify types either on parameters to or return values from a function.

A Final Thought on Dynamic Typing

Some people prefer the more relaxed nature of dynamic typing, and some even argue that it makes programming more productive. I understand that, especially in a proof-of-concept or sandbox mode, it is easier to not have to define variables. But I disagree with the productivity claim, and I have a very simple example that will illustrate my reasoning. Let's make the equivalent single-line change to both the Java and the PHP code:

Java: square.setSize("hello");

PHP: $square->setSize("hello");

What happens? Well, because of the type mismatch, in Java this code does not compile. That's crucial. You can't even run this code. In PHP, however, you can run the code; type mismatches may cause a run-time error, but you can still run the code. Actually, in this case, you won't even get a run-time error; you'll get a value of zero, because PHP tries to convert the word "hello" to an integer and then silently fails. It's universally accepted that run-time errors require much more time to repair than compile-time errors: the more your compiler catches, the less you have to debug.

So back to the premise of the article. How hard is Web programming? Is one language harder to learn than the other? I don't believe that. Since the syntax of the two languages is nearly identical, any claim that PHP is easier to learn than Java seems to be a little bit hard to justify. So the next difference would be how easy the language is to use, and that pretty much boils down to the dynamic vs. static typing. I suppose that can be at least partly a personal preference. In the end, it really comes down to the old adage of "pay me now or pay me later." You may be able to bang out code a little quicker when you don't have to worry about variable types, but it might bite you in the end when a subtle error that would have been caught by static typing makes it into the run-time.

as/400, os/400, iseries, system i, i5/os, ibm i, power systems, 6.1, 7.1, V7,

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online