The IBM i Audit Journal contains a wealth of information yet remains a mystery to those who can use it most. Carol describes practical ways that security and system administrators can use this information to help them in their daily jobs.

The past few weeks, I’ve found myself helping our clients solve their issues by looking for specific entries in the audit journal. Most administrators think that the IBM i audit journal is only good for compliance reporting or just used during a forensic investigation. Nothing can be further from the truth. So I thought I’d share a few examples of how you can use the audit journal to solve daily problems. Or to help you debug problems or investigate administration-related issues.

Tip #1

Ransomware and malware are threats facing every organization. One way to help reduce the damage malware can do is to reduce the *PUBLIC authority to root and other directories. The recommended setting for the root directory is DTAAUT(*RX) OBJAUT(*NONE), which is the equivalent of *USE. *USE allows processes to go down to the next subdirectory or read the contents of the directory but not create directories or rename existing ones (renaming directories is one of the malware variants I’ve seen hit IBM i shops recently). Before you reduce the authority of root to *RX from the default of DTAAUT(*RWX) OBJAUT(*ALL), you’ll want to make sure that no processes are currently writing files directly into root. We’ve seen a few email processes write a temporary file into root and then almost immediately delete it, so you’ll rarely see these files when you view the contents of root in Navigator for i or the green-screen Work with Links (WRKLNK) display. To make sure you’re not going to break a process by removing *W (write) authority, you’ll first want to look in the audit journal.

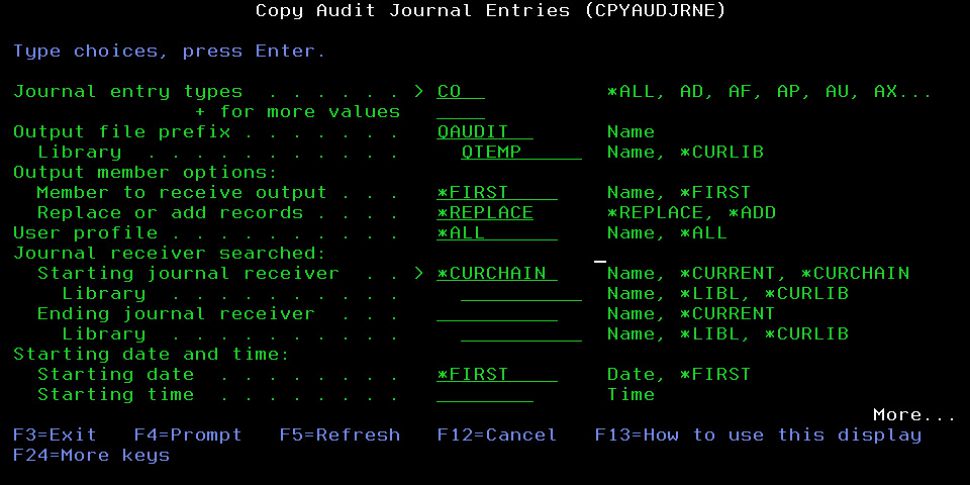

Before I go further, I must explain how I generally get information out of the audit journal. My preferred method of obtaining audit journal entries is to use the Copy Audit Journal (CPYAUDJRNE) command. This command takes the two-letter audit journal entry type that you want to investigate and creates a file in the QTEMP library named QAUDITxx (where xx is the two-letter code.) From there, you can write a query or use SQL to find the information you’re looking for. (Note: If you’re unsure of the two-letter audit entry type you need to specify, press F1=Help on the Type field for a list and description.) See Figure 1.

Figure 1: Obtain audit journal entries by using the CPYAUDJRNE command.

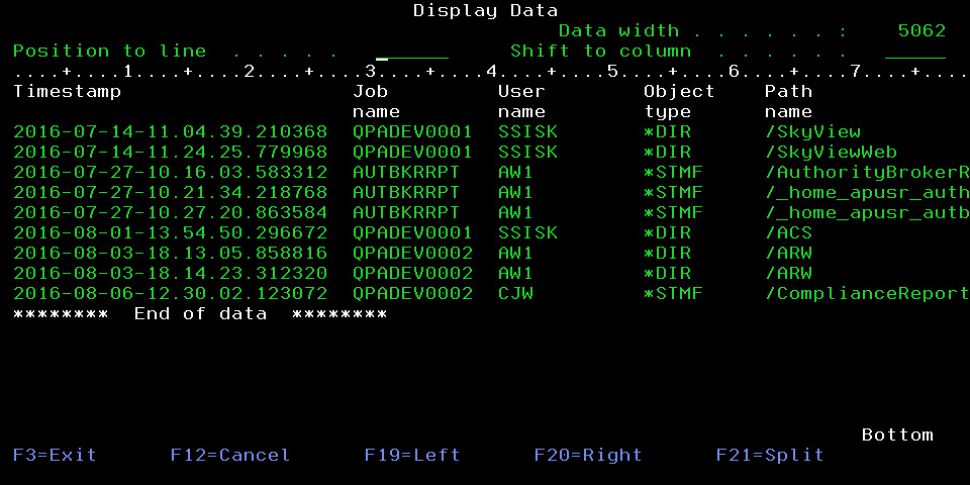

Back to my example. To find processes writing directly into root, you’ll need to examine the CO (Creation of Object) entries. Run the CPYAUDJRNE, going back as far as your journal receivers allow. Once the command has run, look in the Pathname field for objects created into root. My SQL statement looks like this and the results are in Figure 2.

SELECT COTSTP, COJOB, COUSER, COOTYP, COPNM FROM qtemp/qauditco

WHERE copnm not like '/%/%' and coonam = '*N'

Figure 2: Find processes writing directly into root.

In this example, you’ll want to make sure that the people creating new directories are part of your team, not individual users. And you’ll want to understand why there are streamfiles being created directly into root.

Tip #2

One client was trying to determine who created a specific profile and how. He looked through the DO (Deletion of Objects) audit journal entries. In this case, he couldn’t find any entries. Sometimes, the absence of audit journal entries is just as valuable as their presence. In this case, it proves that something didn’t happen and that the investigation needs to take another approach. Had the profile actually been deleted, the audit journal would have shown the job in which the deletion occurred as well the profile performing the deletion. DO entries show more than just deleted profiles. A DO entry is generated whenever any object is deleted. I’ve worked with many administrators to use the DO entries to determine who deleted many types of objects (from programs to streamfiles in the IFS) and when.

Tip #3

I’ve been asked many times if there’s a tool that will list IBM i profiles users with weak passwords. While there’s a report that lists profiles with a default password (the password the same as the profile name), there’s no tool that examines passwords to determine its strength. Of course, if all users changed their passwords using the Change Password (CHGPWD) command, you really wouldn’t have to worry about the issue of weak passwords. To successfully change one’s password using CHGPWD, all password composition rules as defined in the QPWD* system values must be met. Weak passwords are introduced when administrators or help desk personnel enter a weak password when creating or changing a user profile using the Create or Change User Profile (CRT/CHGUSRPRF) commands.

In V7R2, you can force all profiles—even those specified on the Create and Change User Profile (CRT/CHGUSRPRF) commands—to meet your password rules if you add the *ALLCRTCHG value to the QPWDRULES system value. But prior to that, you can examine the Create/Change User Profile (CP) audit journal entry. The Password Composition Conformance (CPPWDF) field in that entry indicates whether the password specified meets the password rules. The two values you typically see for this field are *PASSED, meaning that the password meets all of the password composition rules defined in your system values, and *SYSVAL, meaning that the password does not meet one or more of the rules.

Tip #4

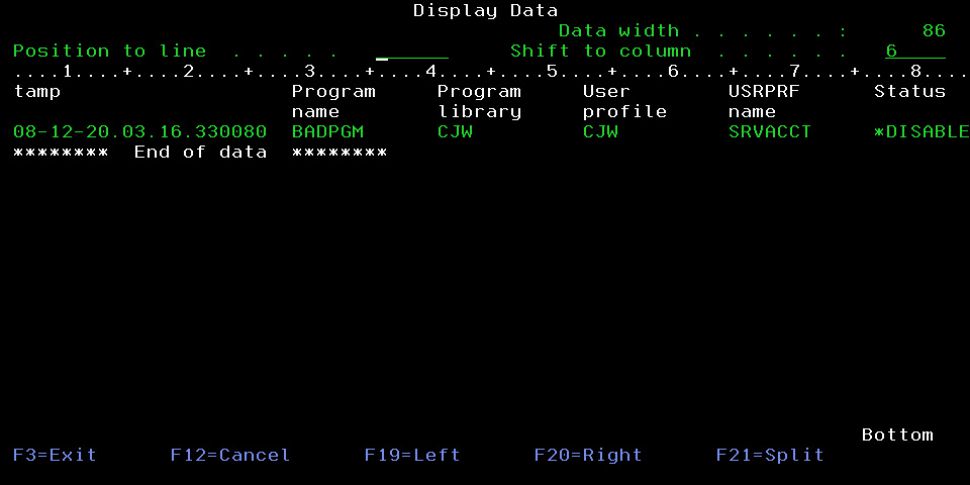

Have you ever had a service account get set to a status of *DISABLED? Outages of websites or other critical interfaces usually occur. You need to determine how this occurred so that you can prevent it from happening again. Once again, the CP audit entry is your friend. Run CPYAUDJRNE using a timeframe that allows you to search from a time when you know the process was still working until just after the outage occurred.

My SQL to find the audit journal entry looks like the code below with a result shown in Figure 3.

SELECT CPTSTP, CPPGM, CPPGMLIB, CPUSPF, CPONAM, CPSTAT FROM

qtemp/qauditcp WHERE cponam = 'SRVACCT'

Figure 3: Find service accounts that are set to *DISABLED.

You can include more information in your Selection criteria—for example, you might find the job information helpful in debugging this issue.

Tip #5

Another scenario that I’ve witnessed is the following: An organization has a service account that is used to make multiple connections to IBM i from other servers throughout their network. The service account has been defined to have a non-expiring password, but the organization’s policy demands that the password be changed annually. The password is changed on IBM i and on all of the servers with documented connections. However, the service account is being used for a connection that wasn’t added to the documentation; therefore, that server’s connection script is not updated with the new password. That evening, the undocumented server attempts to connect, but it fails because it’s passing the old (now invalid) password on the connection attempt. The connection is attempted multiple times, and the profile named on the connection gets disabled on IBM i. In this case, the PW (Password) audit journal provides the information you need to debug the situation. Analysis of the PW entries will show invalid sign-on attempts for the profile. When you examine the Remote Address (PWRADR) field of the entries, you’ll see the IP address from which the request is being made. If you don’t already recognize the IP address, you can do a reverse DNS lookup to find out where (which server) the request using the invalid password is coming from.

The following SQL will provide this information:

SELECT PWTSTP, PWRADR, PWTYPE, PWUSRN FROM qtemp/qauditpw WHERE

PWUSRN = 'CJW' and PWTYPE = 'P'

.

Who Knew?

I hope these tips have made you realize that the audit journal is useful for things outside of its typical use. For more information on IBM i audit features, see Chapter 9 and Appendix E and F in the IBM i Security Reference manual or Chapter 15 in my latest book, IBM i Security Administration and Compliance: Second Edition.

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online