There has long been the belief that the AS/400 and iSeries are secure systems. While it’s true that the AS/400 and iSeries (hereafter referred to only as iSeries) is still the most secure processor in the world, we are now in an era of open systems. That means that the iSeries is just not as secure as it once was. In this edition of Security Patrol, I will attempt to expose for you, the areas of weakness in the iSeries security. I will endeavor to show how a hacker can gain access to an iSeries and how, once that that has been achieved, even more dangerous authority can be gained. I will then show you how a hacker can hide programs and have them launched automatically. Where possible, I will provide solutions on how to stop a hacker from using a combination of exit-point programs, object authority, and auditing techniques.

It’s an IBOD Thing

I would like to introduce to you a character I call IBOD, which stands for Individual Bent on Destruction. IBOD can be an individual outside your organization, or IBOD could be a disgruntled employee. In either case, the first hurdle confronting IBOD is getting into an iSeries. How does he clear this hurdle? Well, I know of several ways—and there may be more.

A common method of getting into an iSeries is to use an existing, well-known, user profile and password, such as the QPGMR or QSYSOPR user profile. Many times companies won’t bother changing the default settings of these profiles, which means that the password for the profile is the same as the name of the user profile. To access your iSeries, all IBOD has to do is type in one of these well-known profiles using the profile name as the password, and before you know it, he’s in. IBOD could also get user profile information from careless colleagues who write their user profile name and password down in some easily accessible area. IBOD could also gain access by using an already logged on, unattended workstation. Another method of gaining unauthorized entry to the iSeries is to look on your company’s bookshelf for vendor’s software manuals. Many vendors use known profiles and passwords for installing their software and for providing remote support and record these user profiles and passwords within the manuals. An enterprising hacker may be able to use one of these profiles to gain unauthorized access to the system. There is also the well-publicized Dedicated Service Tools (DSTs). DSTs are the system utilities that let you access your system hardware, such as DASD, and alter its configuration. If IBOD can gain physical access to your iSeries, he can force an IPL by

entering the correct code on the system panel and, during the IPL process, sign on as the DST user and reset the QSECOFR password.

Unfortunately, physical access alone is not the only way IBOD can cause damage. IBOD can even get into your iSeries without signing on. This is accomplished by using Distributed Data Management (DDM).

A Closer Look at DDM

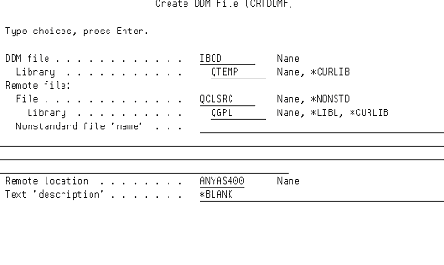

DDM has been around since the days of the System/38. DDM enables you to access files on another connected iSeries. As illustrated in Figure 1 (page 114), a DDM file is created by using the Create DDM File (CRTDDMF) command. You need to specify the Advanced Peer-to-Peer Networking (APPN) name of the remote iSeries, as well as the name of the file you’ll be using as a conduit to pass data through on the remote system. The named file need not exist at the time of the DDM file creation. Along with remote file access using DDM, you can also execute commands on the remote host by executing the Submit Remote Command (SBMRMTCMD) command.

Having created a DDM file that points to a file on a remote host, the act of reading that file through a command such as Display Physical File Member (DSPPFM) evokes a remote session on the remote host. The session will remain open until the session is terminated using a command such as Reclaim DDM Conversation (RCLDDMCNV) or the SIGNOFF command. The remote file that the DDM file is pointing at can even be changed without terminating the session. Moreover, the remote session has its own invocation of the QTEMP library. IBOD can happily load up his programs of destruction into the remote QTEMP library, execute them using the remote command capability of DDM, and then end the session—and there would be no objects lying around to provide evidence of his visit. So, with DDM, the intruder can sneak a peek at files on a remote host as well as execute commands there.

How Is This Possible?

You say it can’t be that easy to break into an iSeries? Surely, IBM would not permit that to happen, would it? Well, it is that easy. However, the truth is that you have very little authority on the remote host. Where the real exposure lies is in situations in which vendors use display station pass-through (DSPT) to provide fixes and enhancements to their applications running on your iSeries. To use DSPT, a vendor needs a valid user profile and password, and an open line to the remote iSeries. Something else to think about is, if a vendor has access to your iSeries, then you also have access to theirs! Moreover, by using DDM, you do not need a password to get into the vendor’s iSeries.

Consider this: If IBOD can get into one vendor’s iSeries, it is possible, if security is lax, for IBOD to harvest user profiles and passwords included in FTP script files resident on that remote host. Moreover, if that vendor’s iSeries uses FTP script files to connect to other hosts, these user profiles and passwords can also be harvested. In this scenario, IBOD could now invade the whole client base of the vendor—and it is very likely that some of these clients also use other vendors’ software programs. This opens up other vendors’ iSeries’ to potential invasion, as well as that of their clients’. And so the process continues....

Invading another iSeries using DDM is like cooking steak and eggs with very long tweezers through the keyhole of the kitchen door—very difficult, but quite possible. As I mentioned before, there is very little authority available to users of DDM. A typical remote DDM session is launched under the user profile QUSER, which normally has very little authority. However, an ingenious IBOD could look around the remote iSeries and find ways to adopt more authority. For instance, IBOD could display user profiles to an output file; with any luck he might find he has operational authority to a user profile that has *PGMR authority. If, when creating a job description, you specify the user parameter with the *PGMR user profile, IBOD can submit jobs with programmer authority and do some

serious damage. Even without additional authority, IBOD can still harvest user profile names and their passwords from a remote host.

Here’s How It’s Done

In my article “FTP: Are You Sure its Secure?” (MC, November 2000), I discussed a file called QADBXATR in library QSYS that contains a complete inventory of all physical files on the system. QADBXATR can be queried to find all source files. Using the underlying search command provided in PDM—the Find String PDM (FNDSTRPDM) command—it is possible to find every occurrence of the word QUIT. Using this technique, every source member that contains an FTP script and, therefore, a user profile and password, could be harvested. This particular attack is just one more in a long string of reasons why passwords should never be stored in clear text in a file.

An Ounce of Prevention

How do you stop IBOD from using DDM to invade your system? The answer is to deploy an exit-point program, such as the one shown in the partial code in Figure 2. Exit-point programs have recently received attention as a method to guard against intrusion. But the truth is, exit points have been around since the System/38 days. In particular, the network attributes feature enables you to specify an exit-point program to interrogate DDM requests. The same facility also provides a similar exit-point program feature for PC Support Access (PCSACC). Do be aware that the PCSACC exit point only protects the old 16-bit PC support servers and does not protect against 32-bit Client Access and Client Access Express servers. Those are regulated through the OS/400 Registration Facility (WRKREGINF). Incidentally, the PC Support (a.k.a. Client Access) remote command facility is a DDM application.

You can execute the Change Network Attributes (CHGNETA) command to specify what action is to be taken when a DDM request is received. You could reject all DDM requests. The factory default is to specify *OBJAUT, which will limit remote users to objects that they are specifically authorized to access and to those objects with *PUBLIC authority. For more information on using this exit point, check out Paul Culin’s article,

“Understanding Exit Programs” in the October 2000 issue of MC.

A Pound of Cure

There are probably more ways to hack an iSeries than you might imagine. Perhaps one of the most notorious is to use DDM. DDM presents a serious security exposure. IBOD can wreak havoc on your iSeries, armed only with the remote system’s APPN name and an open communication line. And, as of V4R3, DDM can also run over TCP/IP, thereby providing yet another possible level of exposure. However, an ounce of prevention and some common sense used in storing user profiles and passwords in FTP script source files, along with using exit programs, can help you to keep your system secure.

REFERENCES AND RELATED MATERIALS

• DB2 for AS/400 Distributed Database Programming (SC41-5702-02, CD-ROM QB3AUD02)

• “FTP: Are Your Sure It’s Secure?” Trevor Seeney, MC, November 2000

• “Understanding Exit Programs,” Paul Culin, MC, October 2000

Figure 1: A hacker can use DDM files to cause problems on remote systems.

/*************************************************************/

/*Parameter Descriptions:- */

/* Rtncde:- '1' OK, '0' Not OK */

/* */

/* Field Format Size */

/* ParmDS:-User Profile Name Char 10 */

/* Application name Char 10 * */

/* Object Name Char 10 */

/* To Apply:- */

/* CHGNETA DDMACC(NO_IBOD) */

/*************************************************************/

PGM PARM(&RTNCDE &PARMDS) /* Pgm: NO_IBOD */

DCL VAR(&RTNCDE) TYPE(*CHAR) LEN(1)

DCL VAR(&PARMDS) TYPE(*CHAR) LEN(30)

IF COND(%SST(&PARMDS 1 10) = 'IBOD' *OR +

%SST(&PARMDS 21 10) = 'COMMAND') +

THEN(CHGVAR VAR(&RTNCDE) VALUE('0'))

ELSE CMD(CHGVAR VAR(&RTNCDE) VALUE('1'))

RETURN

ENDPGM

Figure 2: You should consider using exit-point programs to monitor DDM access.

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online