It may possibly be the stupidest acronym yet invented. It's a takeoff on hi-fi, which stands for high fidelity, which is used for radio, which is by definition wireless, which makes the word "wireless" redundant. (Yes, I know that high fidelity is also about audio and video recordings, but I do so enjoy a good rant.)

However, what else would you call it? Wireless LAN doesn't cut it, and the various specification names like 802.11b just don't seem to catch on the way they did in the old days (like RS232--remember that?). We don't even seem to link manufacturers to their technologies (Hayes meant smart modems, while USR was synonymous with 56K). The closest is Linksys, which is not quite a household name.

So WiFi it is. And these days, you have to have it, whether it be in the workplace or the home. Now, I don't profess to be a corporate network guy (shudder); that sort of thing is best left to people who not only understand the difference between a hub and a switch, but can probably build either one from scratch. But I did recently set up wireless in my own home, and in this column I'll take you on that magical journey, giving you a few tips along the way.

Today's column focuses on two topics: physical setup and security. I won't go into any great detail (as I said, IANANG), but I think just the things I had to learn in order to deal with my own personal issues will be a good starting point for those of you wanting to get your feet wet with wireless.

I added wireless capabilities to my house for about $150 in hardware costs. I bought a wireless network kit from Linksys for $99 (this included a router and a notebook adapter), and later I purchased a wireless adapter for my wife's desktop computer for $49. Add $5 for a crossover cable, and the total was $153. Time was a bit more expensive than I would have liked, due partly to a couple of false starts, but once I got everything running properly, it really wasn't that difficult. And I'm quite confident that I'll be able to extend the network without nearly the same amount of work.

Physical Setup

There are two components for a wireless network: the router and the adapter.

BRZZZT! WRONG! But thank you for playing our game!

My first problem was that I didn't know that there are actually four types of components for a wireless network. There are indeed routers and adapters, but two other components also exist: the access point and the bridge. The difference between an access point and a router wasn't clear until I actually understood how the pieces work, and that understanding didn't come until I looked carefully at the different network options. Therefore, this column will start with topology and move on from there.

As I explain the various topologies, I'll also introduce the primary terms in the wireless vocabulary: router, adapter, access point, and bridge. Learn these terms; they will be crucial in determining what is needed to get your own network up and running.

Components

First, here's the basic vocabulary:

WiFi Adapter: This is the card or USB connector that you plug into a computer to wireless-enable it.

WiFi Access Point: This device allows computers with wireless adapters to talk to a wired network. It is physically connected to the wired network. For Internet access, the wired network must be connected to the Internet via a router.

WiFi Router: This is a device that acts as both a router (to connect to the Internet) and an access point, all in one. Wireless devices can connect to it and, through it, access the Internet directly. Wireless routers usually have a few ports for wired connections as well.

WiFi Bridge: A bridge allows devices without WiFi adapters to connect to a wireless network. A common use is to connect two wired networks.

Basic Topologies

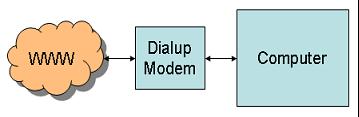

Back in the Copper Age, your network looked like this:

Figure 1: This is a typical single-computer dial-up connection to the Internet. (Click images to enlarge.)

This worked fine, provided you didn't mind the beeping, booping, and screeching, which is acceptable at home, but a bunch of devices in an office setting could get pretty annoying pretty quickly.

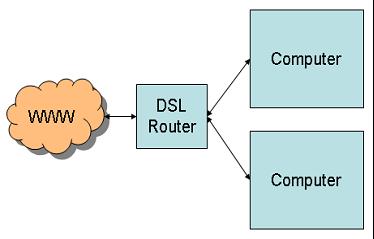

The next step was some type of high-speed router that could connect multiple devices to the same high-speed interface, preferably one that was always connected, such as DSL. A typical DSL connection looks like this:

Figure 2: This figure shows a standard multiple-device hookup, in this case using DSL.

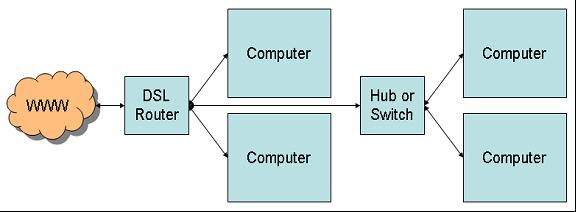

This is great, except that the router typically doesn't have a ton of ports. Its primary purpose is to connect a bunch of devices to the network and perhaps to act as a firewall. It may also hand out IP addresses using DHCP. But as pointed out, its shortcoming is limited connectivity. A typical router has four ports; some might have 8 or even 16. Hooking up a larger number of devices requires a hub or a switch, as shown below:

Figure 3: A hub or switch can be used to extend the network to more devices.

This is also the case when you have long distances to cover. For example, you may have a couple of computers at one end of the house and the router at the other. Rather than run multiple long cables from the router to each computer, you run just one cable from the router to a hub or switch and then connect the other computers to the switch.

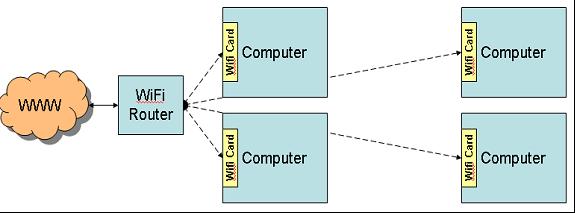

This sort of hardwiring works relatively well when you have clusters of computers, but it's not nearly as good when you have computers in different parts of the building. This is where wireless networks come in. In the simplest scenario, you simply attach a wireless card to every one of your computers, like so:

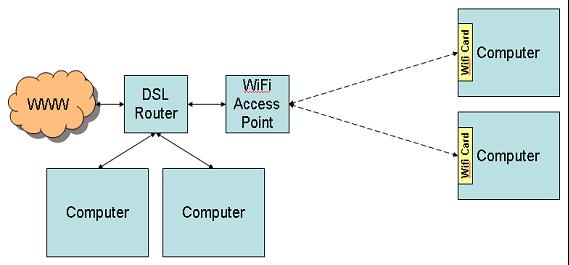

Figure 4: Here you see each computer with an adapter, in this case a WiFi Card.

The WiFi card for desktop computers is only one type of WiFi adapter. There are also PCMCIA adapters for notebook computers and even USB-based adapters that don't require an empty card slot of any kind. The problem here is twofold. First, any of these adapters add a lot of hardware cost, typically $60 to $100 per computer, depending on the speed. Second, the wireless adapters don't have near the speed capabilities of the hardwired network. The current generation of hardwired Ethernet runs at a speed of one gigabit per second, as opposed to the highest wireless speed of 54 MB; that's a twentyfold difference, which can have a huge effect on things like backups.

One way around that problem is the so-called "mixed media" network, shown in Figure 5. With this setup, several computers can share a high-speed wired connection, while the access point provides a sort of gateway for the wireless devices to connect to the wired portion of the network.

Figure 5: This is a typical "mixed media" network.

For example, the two computers on the left of Figure 5 may serve as backups to one another or may share resources. In that case, they take advantage of the high-speed connectivity of the hard-wired connection to communicate with one another. The other computers in the network may not need such a fast connection.

This is similar to the setup in my house. There is a primary network of computers that are located together and hardwired in a fast Ethernet network, and then there are standalone laptops or small form factor (SFF) computers throughout the house used for connecting to the Internet. Since our Internet connection is not a T3 line (44 MB), it doesn't matter that we're running wireless rather than hardwired.

Note: Those who have been paying close attention may have noted a minor discrepancy: I said that I had purchased a router, not an access point. And while this is true, it turns out that my Linksys router can be used as an access point by turning off some features and connecting it to the network with a $5 crossover cable. I don't know if all routers can be used this way. Be careful, and if you buy from a brick-and-mortar store, ask questions.

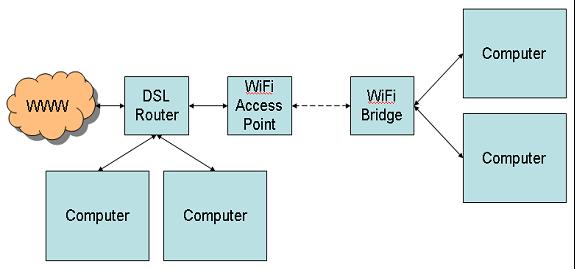

There is one other setup that might make sense. It's really a variation of the setup shown in Figure 3. If you have clusters of computers that are geographically segregated in such a way that it's difficult to run cable between them (this might happen in adjacent buildings, for example), you could feasibly use a wireless bridge to connect them as shown in Figure 6:

Figure 6: Here is the setup for a wireless bridge between hardwired clusters.

Setups like this can go from a few hundred feet to a few miles, depending on your equipment and whether or not you have access to tall towers. The longer-distance stuff is way beyond me, requiring knowledge of decibels and watts and antennas and amps and all that good stuff. I do know that standard wireless covers a house quite well, and if I needed to put a small wired network anywhere else in the house, a bridge would be just the ticket.

Speed

The speed of your network depends on the type of wireless connection. Nearly all wireless networks use the 802.11 standard. The problem with the 802.11 standard is that there are so many of them!

The basic 802.11 standard was hammered out in 1997, and not long after came the 802.11b standard, which is the primary one in use today. 802.11b has a number of characteristics. It runs at 2.4 GHz. This is an unregulated frequency, which means it's susceptible to interference from microwave ovens, cell phones, and other appliances. The theoretical indoor range of 802.11b is about 150 feet, but in reality it seems to be more like just over 100 feet. And its theoretical speed limit is 11 MB/sec, but practical limitations of efficiency and protocol design limit it to a useful rate of 6 MB/sec.

Meanwhile, the newer 802.11a standard has completely different characteristics. Running at 5 GHz, it avoids interference from appliances although at a production cost premium. It's speed is much higher, with a theoretical/practical limit of 54/30 MB per second. At the same time, its useful range is roughly a third of what 802.11b offers.

The third protocol standard is 802.11g, which is sort of a hybrid. It combines the faster speed of 802.11a with the longer range of 802.11b. Since it uses the same 2.4 GHz band as 802.11b, it has the same interference issues, but that allows it to work at a somewhat reduced cost as compared to 802.11a (although still higher than 802.11b). And the best feature is that 802.11g routers are compatible with 802.11b adapters.

If you already have a network and you just want to extend it wireless, I'd suggest the less expensive 802.11b solution: Go with the longer range and slower speed of the 802.11b, and just avoid surfing the 'net near the microwave. The Linksys Wireless-B Network Kit is a router and notebook card for $100. This allows you to connect a laptop to your network. After that, additional Linksys adapters for other computers cost about $60.

Then, if you outgrow the speed of that network for some reason, you can move to the 802.11g standard. As I understand it, you can replace the 802.11b router with the 802.11g, and it will talk to both 802.11g and 802.11b devices. Thus, you can upgrade the individual adapters in your network as necessary, rather than having to do them all at once as you would if you went to the 802.11a standard.

You may be asking, "What happened to 802.11c through 802.11f?" Actually, these parts of the standard exist, but they're related to areas other than speed. For example, 802.11f deals with how access points hand off a roaming signal. These portions of the standard concern manufacturers more than end users, so we won't hear much about them.

Security

Security is a huge topic. I will only be able to introduce you to the basics of WiFi security in this column. If you're interested in more information, let me know in the forums and I'll report in more depth. For the purposes of this column, however, I'm just going to cover the topics at a fairly high level.

In general, WiFi components ship unsecured. In fact, if you install a WiFi network with out-of-the-box components and then fire up one of your newly wireless computers, it may even tell you that you're connecting to an unsecured network (at least that's what XP Home does). What does this mean? Well, generally it means that anybody can get on your network. They can't necessarily do anything, but they can get on it.

DHCP

Security is one reason that I prefer static IP addresses to DHCP, by the way. With static IP addresses, users have to sniff the network to guess the appropriate range and then manually assign themselves an address, hoping it does not collide with an existing address. To go surfing, they also have to figure out the address of the gateway, which requires more sniffing, and then select a DNS server. With DHCP, that's all done magically for you! This isn't a huge issue, and here's the trade-off: more work whenever you add a new computer to the network vs. a little added security. It's worth it to someone like me who believes in non-addressable addresses and yet still locks down FTP with an exit point. (Not only that, I shut off FTP when I'm not using it!)

It turns out that in the wonderful world of WiFi, these precautions are no longer such a bad idea. As I said, as configured from the factory, WiFi networks are wide open. That makes installation easier perhaps, but it also means that basically anybody who drives past your house or business is (theoretically) on your network. If you don't provide DHCP, it's that much harder for them to connect to your network. And if you protect your assets as if bad guys had already stormed the gates, then you're far less vulnerable to "war drivers" (folks who drive around looking for unsecured WiFi networks).

Network ID Broadcast

This is a high-tech way to let intruders know there is a network in the area. It's kind of like putting a big bullhorn on your house that continually shouts, "The back door is open!" Unless you're planning on running your own Internet café, shut it off. Unfortunately, some software can't connect to a wireless network unless it is broadcasting, so this may not be an option for you. And a determined hacker can find your network ID by just watching the network traffic around your location.

WEP and WPA

These are the basic standards for WiFi network security. Wired Equivalent Privacy (WEP) is the older standard, and it has some vulnerabilities in the header structure that make it relatively easy to crack. Wi-Fi Protected Access (WPA) uses a better encryption algorithm, but it's not supported by all components (especially older, less expensive 802.11b components). You'll have to check your components to determine which is the correct security for you. Just remember that running with no security is like letting people walk into your computer room and jack right into your network.

MAC Addresses

A very nice added support mechanism is medium access control (MAC) address filtering. With this capability, you can specify which MAC addresses can access your network. Since the MAC address of each adapter is unique, this would in theory provide ultimate security. Unfortunately, in real life it's relatively easy to spoof the MAC address, so anybody with a packet sniffer would be able to determine a valid MAC address and spoof it.

Not to put too negative a point on it, but basically if you have a wireless network set up, there's almost no way to stop a determined hacker from getting in. The best way is to limit the access to the wireless network itself by carefully positioning your wireless access points to limit outside access and maybe even using the shorter-distance 802.11a standard.

For home systems, just keep an eye out. If someone you don't know is sitting on your porch with a laptop, you may want to find out why. Seriously, though, unless someone is parked outside your house, there's little chance they're using your network. Check your logs and look for unusual activity, and always treat your network like it's wide open--not a bad idea even without the added security risk of a wireless connection.

Wrapping It Up

I am still having some problems setting up security on my end. Bits and pieces still need to be worked out, and the process has certainly been educational. The whole WEP vs. WPA thing is interesting, as is the fact that two different installations of XP Home have completely different screens for handling the security setup--and one works, while the other doesn't. Is it hardware, software, or brainware errors? We'll find out.

When I get everything worked out, I'll let you all know. And if you're really interested in more about WiFi security, please drop a line in the forums or contact me directly: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Joe Pluta is the founder and chief architect of Pluta Brothers Design, Inc. He has been working in the field since the late 1970s and has made a career of extending the IBM midrange, starting back in the days of the IBM System/3. Joe has used WebSphere extensively, especially as the base for PSC/400, the only product that can move your legacy systems to the Web using simple green-screen commands. Joe is also the author of E-Deployment: The Fastest Path to the Web, Eclipse: Step by Step, and WDSC: Step by Step. You can reach him at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online