Python is no slouch when it comes to access capabilities—the immediate system (PASE) and the IBM i system. So we’ll do “ice cream before spinach” and take a look at PASE access first. It is probably better thought of as “host” system access since calling (shelling) out to the system can be done in LUW as well as PASE.

Editor's Note: This article is excerpted from chapter 9 of Open Source Starter Guide for IBM i Developers, by Pete Helgren.

For the previous two articles in this series please see Programming in Python, and More Programming in Python.

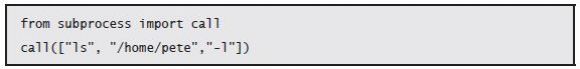

In Python, here is how we begin the “Journey to the Center of the i”: We use subprocess… call to get there.

Basically, the script spawns a new process, executes the command, and then returns the output. Nothing fancy here. It is very similar to many other scripting languages. Where things get interesting is when you access IBM i resources. We can pretty much get to whatever we want on IBM i by using the XMLSERVICE library. Fortunately, Python also has a wrapper module in the iToolkit for Python. Let’s take a look at this particular implementation of the Python client of XMLSERVICE.

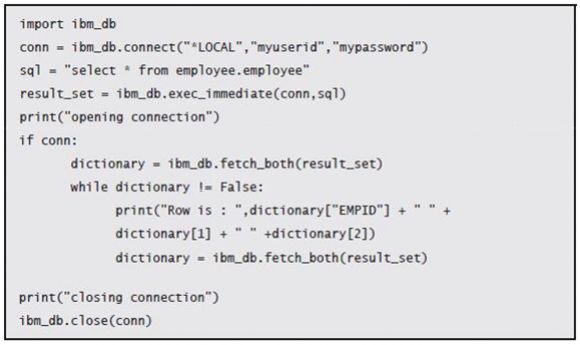

DB2 Access

Again, we are fortunate to have the pioneers of open source doing all the heavy lifting for us on IBM i. There is already a Python module called ibm_db that handles all the I/O to DB2 on i and back again. All we need to do is use it.

Just an aside on getting the functionality. I went the PTF route in order to get the ibm_db and the iToolkit installed for Python. I also chose to install it for Python 3. I hate to give you links to the site because they get outdated so quickly, but I pulled the instructions from the IBM developerWorks site, which used pip3 to install the wheel (.whl) file.

It seems that is the currently supported method. So plan on installing the correct PTF for your level of the operating system as well as installing using pip3. That sounds redundant, but it is not. pip3 installs from the IFS, but there isn’t anything there unless you install the PTF first! So find the PTF, install the PTF, and then install the .whl using pip3. That worked for me.

Once you have the ibm_db module installed, you can use it. Let’s look at an example in Python 3. (How do you know it is Python 3? The print() statements.)

Note that in the dictionary that is returned, I can reference the columns by name or by ordinal position (dictionary["EMPID"] or dictionary[1.... ] ). Plenty of I/O methods are available, so we are looking at only one here. But we used the “generic” ibm_db.exec_ immediate, which we could use for any SQL statements: SELECT, INSERT, DELETE, and so on. And, of course, there are methods that will allow us to bind parameters and execute prepared statements. The whole panoply of SQL goodness is available to you here. I encourage you to experiment (with a test database, of course).

Accessing RPG

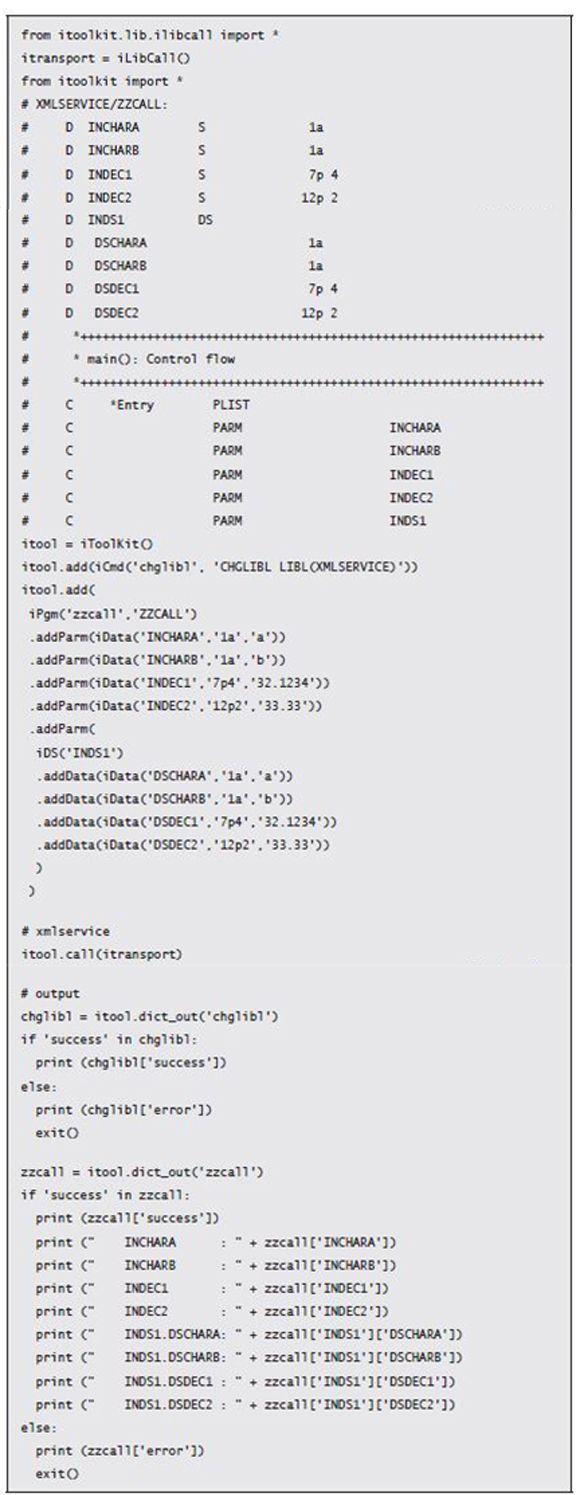

Once again, we have “one call, that’s all” for calling RPG from OSS, and that is: XMLSERVICE! Of course, you know this stuff! You’ll need to make sure that the toolkit is properly installed using the same procedure as with the ibm_db module. But once you have the toolkit installed, there is just one thing to remember: require toolkit! Here is an example (similar to the others if you have read the other chapters):

TMI! Let’s unpack it because there is a bunch of scripting that adds to the verbosity when the actual action in the example is pretty simple. Import commands. We have two. The first pulls in the iLibCall method from the package itoolkit.lib.ilibcall. We then assign iLibCall to a variable (object) called itransport. iLibCall will use the XMLSERVICE library to make the direct call using the current connection (in my case, made using a shell in SSH). We can also use a DB2 stored procedure or a REST call using HTTP if we need to call into a remote system. The second import pulls in all methods from the itoolkit package. It isn’t redundant because we won’t get every method from every package with from itoolkit import *. We only get the methods and objects from the package. Import pulls in what we need from the itoolkit module.

The endless comments are just to show you the code that will be executed by the call. It will give you the program structure so you will know how to structure your own program call. It is just comments. Don’t sweat the verbosity, OK?

Next, we create an itool object that contains most of the code to do the heavy lifting for us. Once we have that object, we immediately use it to add a command (an iCmd object cleverly called chglibl) to add XMLSERVICE to the library list. Then we add an iPgm object called zzcall to the itool object. The definition of that iPgm object has multiple parameters called iData objects that define the single-variable parameters and parameters called iDS objects that are data structures. But rather than adding parameters to the iDS object, you add data objects to the data structure. Logical, right?

Once you define the objects, adding them to your itool object, then you make your call using whatever transport you defined (direct, DB2, or REST). All the magic happens there. Now you just have to query the itool object to see if your call was successful. We actually had two things that ran: The CHGLIBL command, and the call to the ZZCALL program in XMLSERVICE.

Now we retrieve the results, storing the results in a dictionary (hash). We know the command was successful if the “success” key is in the dictionary. If we didn’t find “success,” then an “error” key would be available, and we could examine that value to see what went wrong. The same routine applies for our call to ZZCALL (why do I think of bearded guys when I see ZZCALL?). We check to see if our dictionary contains a “success” key, and if so, we retrieve the value, which is the name of the program we called, and then we walk the rest of the dictionary to retrieve the values associated with each parameter. Our print statements dutifully print out the contents of each parameter returned. Lather, rinse, and repeat with your stuff. It is tedious but eminently functional. No pain, no gain.

Feel the Power

What I have been trying to demonstrate in this chapter is the strength of Python: its terseness without being mystifying and its utility and flexibility. For IBM i folks, that should be familiar territory. Our command-line commands are very terse yet, arguably, about as descriptive as a three-letter command can be. The object-oriented nature of Python also appeals to the Java programmer in me. Yes, I see the same kind of power in JavaScript and PHP and Ruby, but it nicely comes together in Python.

LATEST COMMENTS

MC Press Online